Irrational Numbers

By Murray Bourne, 10 Aug 2010

Challenge

Let's start with an interesting question.

Can you construct the length √7 just by using a measuring stick, a pencil and a set-square? (A set-square is a triangular device used for producing right angles.)

Before we answer this question. First, some background on several very important ancient mathematicians and how irrational numbers came to be.

Length of the Hypotenuse

In the 5th century B.C., mathematicians were fascinated - yet exasperated - with irrational numbers. They believed the only meaningful numbers were the natural numbers (1,2,3,...) and any ratios involving these numbers (like 5/2, 7/9, etc). So they only accepted rational numbers and any other numbers were "unmeasureable".

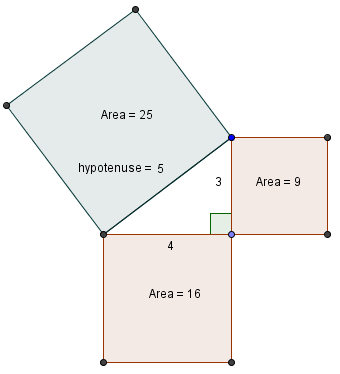

Pythagoras (or someone in his metaphysical school of mathematicians) had shown the famous result that for a right angled triangle, the area of the square on the hypotenuse (in green below) equals the sum of the areas of the squares on the other 2 sides (the 2 light red squares).

You normally see Pythagoras' Theorem written as follows, where c is the hypotenuse and a and b are the lengths of the other 2 sides:

a2 + b2 = c2

In my diagram above, we have the common 3-4-5 triangle. Each number is an integer and for the ancient Greek mathematicians, this presented no problem.

However, since they believed irrational numbers did not exist there was a problem when they extended the Pythagorean formula to other values.

The length of the hypotenuse involved a square root:

![]()

Depending on the values of a and b, we could easily get irrational values for c. How could they measure these distances if they didn't actually exist?

Theodorus of Cyrene

Theodorus of Cyrene was a 5th century B.C. mathematician and was born around 100 years after Pythagoras. (Cyrene is now called Shahhat, in Libya.)

He apparently proved that the square roots of 2, 3, 5, 6 and so on up to 17 were all irrational, except the perfect squares 4, 9, 16. (Unfortunately we no longer have the proofs.) He also went on to construct these supposedly non-existent distances.

He proceeded as follows.

Start with a right triangle with equal sides 1, giving a hypotenuse of √2 (which of course was a problem, because this distance didn't officially exist):

Then, extend a line with length 1 unit (using your 1-unit measuring stick) at right angles to the first hypotenuse as follows. This gives us the length √3 after we apply Pythagoras' Theorem to the new triangle.

Do it again, and you now get the length √4 = 2. Theodorus had discovered one hypotenuse with a rational number length.

He kept going and found that the next one to have a "rational" length was √9 = 3.

He continued on to √16 = 4, constructed one more, √17, then stopped.

And so now you know how to construct the square root of any number using a straight edge, a pencil and a set-square.

Eudoxus

It was one hundred years later when the Greek astronomer Eudoxus (around 370 B.C.) concluded that because we can measure irrational distances (as we did above), then irrational numbers must exist. Problem solved.

Conclusion

It's interesting that throughout history, people have yelled "Impossible!" when some new type of number was proposed. But subsequently, mathematicians have shown that not only are many of those numbers possible, but they have proved to be very useful.

Apart from irrational numbers as we discussed above, people originally did not believe in the existence of the number zero, imaginary numbers and "infinitesimals" in calculus. But in each case, they have been accepted as true numbers and used in many real applications.

See the 8 Comments below.

10 Aug 2010 at 11:50 am [Comment permalink]

Yes,

13 Aug 2010 at 1:40 am [Comment permalink]

it was Good to know more about pythagoras theorem

13 Aug 2010 at 1:52 am [Comment permalink]

Thank you for the great post! I remember learning the method used by Theodorus, but was disappointed it wasn't easier to use it to find square roots of larger numbers. I was very excited to find another method, which only assumes the need for constructing circles or line segments of integer lengths.

To find the square root of a number n, the trick is to draw a right triangle whose hypotenuse has a length of (n+1), and whose altitude drawn from the right angle intersects the hypotenuse 1 unit from the end. The height of the altitude has length equal to the square root of n, since the smaller triangles are similar. It is really the geometric mean of 1 and n.

The fun part is that it's actually very easy to make such a situation! Any right triangle can be inscribed in a circle such that the hypotenuse is the diameter of the circle (and the center of the circle lies on the diameter). So given a segment of length n:

- extend it one unit to get a larger segment of length (n+1)

- find the midpoint of the new segment

- draw a circle centered at that point which passes through the endpoints of the larger segment

- draw a line perpendicular to the segment through the point 1 unit from the end of the diameter

- the point where the perpendicular line intersects the circle is the square root of n units from the diameter

A picture truly is worth a thousand words, and this would have been a relatively easy picture to draw... Sorry if it isn't clear!

14 Aug 2010 at 10:49 am [Comment permalink]

@Jay: Thank you for your input! You are right - a picture is worth a thousand words!

For the more visual of us, here is what Jay suggests:

I have used n=10 and so we'll find the square root of 10 (distance CD):

For the second suggestion:

The height b is the square root of 10.

I used GeoGebra to obtain these diagrams.

14 Aug 2010 at 9:33 pm [Comment permalink]

In Kerala, which is one of the states of India, while constructing buildings right angles for the corners of the walls are obtained by three sticks one with a length of 3 convenient units, another with a length of 4 units and a third having a length of 5 units kept in the form of a triangle when the largest angle will be a right angle. And in fact they are unaware of the Pythagorus Theoram

2 Dec 2010 at 6:23 pm [Comment permalink]

I am most grateful for all that you have been sending to some of us in third world countries. More grease to your elbows.

19 Dec 2010 at 6:29 am [Comment permalink]

I can see why irrational numbers were first thought to be non-existant. Because irrational by its nature means it will continue to get smaller and smaller forever and ever. But, root 2 does exist. Then where does it end really? Is there no way to clearly define a length for an irrational number?

19 Dec 2010 at 7:14 am [Comment permalink]

@Jesse: I'm not sure what you mean by "Because irrational by its nature means it will continue to get smaller and smaller forever". When finding the value of an irrational number, there are processes whereby the you can close the gap between the value of the irrational and some known rational value and so in that sense, the gap gets smaller and smaller.

As for clearly defining length of a distance which is irrational, we have to take the engineering approach - close enough is good enough!