Which is the correct graph of arccot x?

By Murray Bourne, 03 May 2011

A reader challenged me on the graph I had for y = arccot x, on the page Inverse Trigonometric Functions.

He wrote (in a rather unfriendly tone):

Compare:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Inverse_trigonometric_functions

https://www.intmath.com/analytic-trigonometry/7-inverse-trigo-functions.php

You incorrectly state the range of the arccotangent function as -pi/2 to pi/2. It is not. The correct range of arccotangent is 0 to pi.

After some deliberation, I have now included both interpretations on my page, because both are found in various sources.

First, some background.

Obtaining the graph of y = arccot(x)

The graph of y = arccot x can be obtained from a consideration of the graph of y = cot x.

But depending on your starting region, you'll get a different graph for y = arccot x.

Interpretation 1

The graph of y = cot x is as follows:

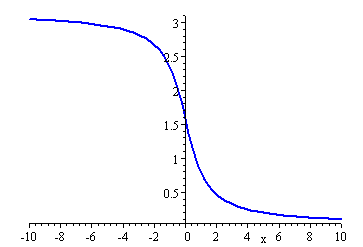

We choose the portion from x = 0 to x = π (as highlighted above), and reflect it in the line y = x like this.

Since reflection in the line y = x gives us the inverse of a function, we have obtained the graph of y = arccot x, as follows:

From the graph we can see the domain (the possible x-values) of y = arccot x is:

All values of x

And the range (resulting y-values) of arccot x is:

0 < arccot x < π

If we evaluate our function for some negative value of x, say x = −2, then we get a positive answer, as expected from the graph:

arccot(−2) = 2.678...

Alternate View - Interpretation 2

Some math textbooks (and some respected math software, e.g. Mathematica) regard the following as the region of y = cot x that should be used (that is, −π/2 to π/2):

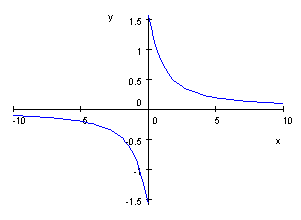

This would give the following discontinuous graph when reflected in the line y = x:

So the domain of arccot x would be (as for Interpretation 1):

All values of x

Using this interpretation, the range of arccot x would be:

−π/2 < arccot x ≤ π/2 (arccot x ≠ 0)

If this is the correct graph, we expect a negative answer when we evaluate the function at x = −2. It is actually:

arccot(−2) = −0.46365...

Which is correct?

According to a response to a reader's question on this same issue, Dr. Math goes for the first interpretation:

In order to invert a trig function, we first restrict it to a domain on which it takes all its possible values, once each; then we invert the restricted function, whose range is then that restricted domain.

Look at a graph of the cotangent function, and you will see that although between -pi/2 and pi/2 it takes all its possible values, and takes each value only once, there is one problem with this choice: it is not continuous (or even defined) on this entire domain, but is undefined at 0.

The domain would then have to be

-pi/2 < x < 0 or 0 < x <= pi/2

To avoid this, we instead choose the domain

0 < x < pi

which is cleaner to work with, making a continuous function defined over the entire domain.

Math software doesn't agree, either

Let's now see the inconsistent way (respected) math software deals with this function.

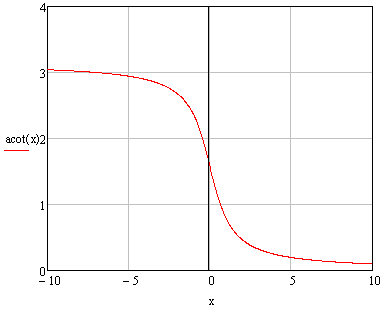

Mathcad's Interpretation

When I graphed the function acot(x) in Mathcad, this is the result (they are using the first interpretation):

Mathcad gives arccot(−2) = 2.678..., which is consistent with their graph. Mathcad uses "acot(x)" notation.

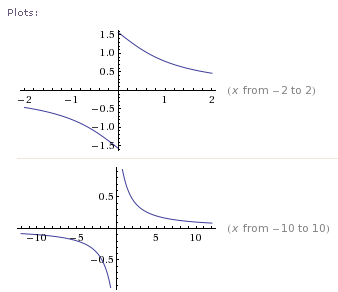

Mathematica's Interpretation

However, according to Mathematica (using Wolfram|Alpha) , this is the graph of y = arccot(x):

So Mathematica is using the second interpretation of the function. (They use the somewhat poor notation y = cot−1x.)

Taking a typical value, Mathematica (Wolfram|Alpha) gives us

arccot(−2) = −0.46365...

How can this be? The first interpretation gives us a positive value for arccot(−2), while the second interpretation gives us a negative value.

Matlab's Interpretation

Matlab also gives us a discontinuous graph based on the second interpretation.

Matlab also uses "acot(x)" notation.

Maple/Scientific Notebook's Interpretation

My version of Scientific Notebook has both Maple and MuPAD engines. The results using both of these are curious.

Using the Maple engine, we get an answer using the first interpretation.

But when we switch to use MuPAD in Scientific Notebook, we get this result, which uses the second interpretation!

So even the top math software makers can't agree.

Conclusion

Here's another case where our math definitions are not as tight as we are often led to believe.

Also, the notation is inconsistent. Different text books and different software use the following to mean the same thing:

- arccot(x)

- acot(x)

- cot−1x

We should never use the last one! (See my rant on this here: Arcsin or sin?)

So which version of arccos(x) is the right one? Is my reader correct? (I don't know his name or email so I can't reply to him. Strange.)

I know which interpretation I think is "best". What are your thoughts?

See the 40 Comments below.

3 May 2011 at 9:19 pm [Comment permalink]

I love this careful, thoughtful discussion! I especially liked your investigation with each piece of math software. Thanks for doing the research.

3 May 2011 at 9:20 pm [Comment permalink]

[...] love this discussion at squareCircleZ. All my readers should check it out. Which is the graph of arccot(x)? from [...]

4 May 2011 at 4:31 am [Comment permalink]

Good catch!

Arccotg(x) is monotonously decreasing in the interval (0,Pi). Monotonous increasing/decreasing functions are "inversable" by one Theorem. Therefore this interval is the logical choice. For the same reason the books choose (-Pi/2,Pi/2) for Arctg(x).

Ah yes, I do think that the correct notation is "arccotg(x)". See we have "tg" (TanGent) and we put "co" in front if it, so we should have "cotg" (COTanGent). Finally put an "arc" in front and it happens to be "arccotg" (ARCusCOTanGent).

Your article is superb!

4 May 2011 at 5:33 am [Comment permalink]

You inspired me. OK, I did some research and I found the answer. The “arccotg(x) in (-pi/2,pi/2) without 0? and “arccoth(x) in (0,pi)” are the inverse functions of TWO DIFFERENT FUNCTIONS. And yes, BOTH ARE VALID.

Let me explain it with x^2. This function is NOT inversible. If you draw a horizontal line it will cross the function in two points. But still we usually say “the inverse function of x^2 is square root of x”. Yes, we do say it wrong! Actually the “square root of x” is inverse function of the following function:

x^2 for x>=0

AND

undefined for x<0

x=0 AND undefined for x<0" is NOT the same function as "x^2 for any x".

It is the same with the trig functions. "cotg(x) in (-pi/2,pi/2)" is not the same function as "cotg(x) in (0,pi)". Therefore their inverses are also two different functions.

Conclusion: it is WRONG to say "the inverse function of sin(x) is arcsin(x)". Well it is not true – sin(x) itself do NOT have an inverse function 🙂

P.S. Fix your blog comments to convert the angle braces < and >. It seems like they do open HTML tags, which is bad. They must be converted to > and <

4 May 2011 at 2:02 pm [Comment permalink]

[...] En este post de squareCircleZ, que es de donde he sacado algunas de las imágenes, hablan también sobre este tema. MeneameBitacorasDeliciousGoogle BuzzFacebookTwitter [...]

5 May 2011 at 4:05 am [Comment permalink]

Thanks for clearly laying out the different approaches. I'm surprised that the computer algebra systems interpret this function differently. I checked a few calculus textbooks, and they agree with how Mathcad defines arccotangent, (acot function in Mathcad).

I'm going to post it for our users to discuss in the Mathcad discussion.

Thanks again,

Mona

Mathcad Senior Technical Consultant

PTC

6 May 2011 at 2:29 am [Comment permalink]

If only they taught this to high school trig students, then perhaps some of the kids would see that their negative preconceptions of the subject are not unjustified. (That is, trig doesn't always make sense!)

Then again, it might show some of them that maths can be exciting and deliciously contentious.

Excellent article!

7 May 2011 at 10:31 am [Comment permalink]

That's really interesting, Valery - thanks for sharing!

It's interesting because:

(1) It is a Mathcad file that is displayed in a browser, and

(2) Yes, many functions demonstrate interesting shapes in polar coordinates.

21 Aug 2011 at 9:41 pm [Comment permalink]

MathCad is right. The other software makers are at fault for not checking it thorough. This issue of detail is one where even an "A" student may overlook.

Maybe the very best graduates end up working for the big banks and big bucks. The math software companies don't agree because they only got the second layer of the top tier graduates to work for them. MathCad was careful (we need to teach work ethic and values), or maybe just lucky.

;-P

29 Nov 2011 at 7:12 pm [Comment permalink]

I found that:

Mathcad 13 works with Interpretation 1

but Mathcad 15 with Interpretation 2 !!

It's a pity !

29 Nov 2011 at 9:38 pm [Comment permalink]

@Richard - thanks for the information. Seems like their engineers are unsure, too!

14 Dec 2011 at 10:16 pm [Comment permalink]

(1) You should always use cot^{-1}(x), following the general notation for functions. This is different from cot(x)^{-1}, of course. Nobody really knows the meaning of arcus sinus etc. anymore.

(2) It is a matter of definition, or rather does not matter at all, what interval we take. If I implemented that, I'd follow your advice to define it on [0,pi], since it is easier. There is no other reason.

(3) If we argue from the geometrical point of view, cot(x) cannot be negative at all. It is the length of one of the segments of the tangent at the point (cos x, sin x). The other is tan(x). By the way, the tangent line intersects the y-axis in cosec(x), and the x-axis in sec(x). In triangle geometry, we wish to avoid negative lengths.

16 Dec 2011 at 5:01 pm [Comment permalink]

@Rene: No, cot^(-1)(x) is one of the worst notations ever, because of the confusion with reciprocal notation. See the last section on this page:

Trig Functions of Any Angle

I like your point about avoiding negative lengths, though.

10 May 2012 at 9:01 am [Comment permalink]

Good discussion, and as someone noted, arccot(x) is not the inverse of cot(x). When we discuss the arccot(x) function as the inverse of another function, we must declare the restricted domain of that function (as we must do with all of the other inverse trigonometric functions).

For option 1, arccot(x) is the inverse of the function cot(x) where x is between 0 and pi.

For option 2, arccot(x) is the inverse of the function cot(x) where x is between -pi/2 and pi/2 (including pi/2, but not -pi/2) and not zero.

Therefore, both interpretations are correct when stated correctly.

Due to the modern calculator (which does not have an arccot(x) function), I prefer the second interpretation because this allows us to easily use a calculator and the identity: arccot(x) = arctan(1/x). This does require one special case when x = 0: arccot(0) = pi/2.

One more thing. You said that one problem with the second interpretation is that the domain does not include x = 0. That is not correct. What the graphs do not show is that the left branch (below the x-axis) has an open circle on the y-axis and the right branch (above the x-axis) has a closed circle on the y-axis. Therefore, the domain of arccot(x) in either case is still all real numbers.

Thanks for your discussion. This is always a confusing issue for students.

12 May 2012 at 8:14 pm [Comment permalink]

Thanks for your clarifications, Ron.

11 Aug 2013 at 12:56 am [Comment permalink]

What is difference between arccot x & cot-1 x

11 Aug 2013 at 9:02 am [Comment permalink]

@Abhik: The first one is much better notation, but normally they are taken to mean the same thing.

See the bottom of this Trig Functions page where I explain further.

27 Jan 2014 at 1:41 pm [Comment permalink]

Thanks for this article I am teaching trigonometry and I came across this issue of trying to figure out which arccot(x) graph to teach and am relieved to have the answer using this article. Thanks for the research

1 Mar 2014 at 2:30 am [Comment permalink]

Thanks a lot for your detailed explanation. I was wondering if there is any way to get the first interpretation with Mathematica? I mean how can we graph a ArcCot in Mathematica in order to get the graph that is look like the first example(0 < arccot x < ?).

Thanks

1 Mar 2014 at 10:14 am [Comment permalink]

@Saman: You could plot the following 2 graphs on the one axis and get what you need:

f1(x) = pi + ArcCot for x < 0 f2(x) = ArcCot[x] for x ≥ 0

19 May 2014 at 9:47 pm [Comment permalink]

Hi

How do you acomodate the trigonometric identity

ATAN(X) + ACOT(X)= PI/2 (PI=3.14......)

You see simmilar to

ASIN(X) + ACOS(X) = PI/2

I can see the first interpretation looks the answer.

20 May 2014 at 7:42 pm [Comment permalink]

@Miguel: Yes, you are right. It would have to be the second interpretation.

18 Nov 2014 at 10:33 am [Comment permalink]

why is that people use the principle interval (-pi/2, pi/2] in the first place

18 Nov 2014 at 11:44 am [Comment permalink]

@Buzz: A lot of these things are due to convenience. Some problems work better with one interval and not the other.

13 Apr 2015 at 10:24 pm [Comment permalink]

This is all based on what you consider to be a "natural" choice for the domain. So far it seems that everyone in the discussion has been valuing continuity and "simplicity" so they are opting for the 0 to Pi range.

If we are sticking purely to real-valued numbers this makes sense, but the 0 to Pi range is an entirely unnatural choice for complex values. The source of the -Pi/2 to Pi/2 choice comes from finding the solution to the complex valued equation: z = Cot[w]. If we represent Cot[w] as Cos[w]/Sin[w] and then replace the sine and cosine functions with their complex exponential representation and then solve for w we get the equation:

w = ln((z+i)/(z-i))/(2i)

where ln is the complex logarithm. This is usually used as the definition of the complex arc-cotangent.

For real numbers (x+i)/(x-i) has magnitude 1 and the logarithm becomes the Argument multiplied by i. If you graph the function

Arg((x+i)/(x-i))/2

you'll see that you get the Interpretation 2 graph. This is equivalent of a branch cut choice of (-i,i). You'll also see that when evaluated at 0, you get Pi/2.

Due to the close relationship between how functions behave on the real number line due to the structure of the complex plane, I think it's quite natural to favor the definition based on the restriction of the complex definition to the real number line.

14 Apr 2015 at 11:57 am [Comment permalink]

@Kevin: Thanks for the complex numbers interpretation. It seems to have the most weight so far.

19 May 2015 at 1:58 am [Comment permalink]

I think the first interpretation - the one that gives the continuous function - is the better one to chose.

26 Jun 2015 at 10:06 am [Comment permalink]

I originally would have said the arccot graph is the discontinuous one. however I ran into a problem with that approach in that if two functions have the same derivative, the function must differ by a constant.

Since y=arctanx and y=-arccotx have the same derivative [1/(1+x^2)]; they must differ by a constant. your way will make this work. the constant will be pi/2. my original discontinuous way will be a mess.

26 Jun 2015 at 7:33 pm [Comment permalink]

@Barry: Thanks for sharing your thoughts on this.

Are you any relation to Sol? http://wildaboutmath.com/about/

26 Jun 2015 at 9:00 pm [Comment permalink]

@Barry

The issue of the derivative doesn't support one interpretation over another. The derivative by definition is a local property of a function and doesn't necessarily tell us about the global structure of a function except under very specific circumstances. That's why two different Lie groups with very different global properties may share the same Lie algebra (The connection may seem strained, but lie algebras are tangent spaces for lie groups, and tangent spaces arise from derivatives).

The proof for two functions sharing a derivative implying they are the same function different by a constant relies on the difference of the two functions being a differentiable function. The proof goes something like this:

Let f and g be two differentiable functions that share derivatives on the interval (a,b). Then h = f-g is also a differentiable function on (a,b). Further h' = 0 on (a,b) which implies h is a constant function. Therefore, f and g differ by a constant on (a,b) QED.

Note: the open intervals are necessary for the limit to be approached from both sides

The discontinuous ArcCot[z] does not satisfy the requirements of the theorem (discontinuous functions are not differentiable at the discontinuity), therefore the theorem does not apply here. HOWEVER, we can break this into two separate regions: (-inf, 0) and (0, inf) and show that on these intervals -ArcCot[z] and ArcTan[z] are both continuous with matching derivatives. And in fact on the first interval they differ by -Pi/2 and on the second they differ by Pi/2.

13 Oct 2015 at 9:02 am [Comment permalink]

@ Barry:

In support of Kevin, the full theorem is

IF f and g are continuous on [a,b] and differentiable on (a,b) and if f'(x) = g'(x) on (a,b)

THEN f(x) = g(x) + C on (a,b)

which is proved by the MVT requiring continuity and differentiability.

And since f(x) = arccot(x) with range (-pi/2,0)U(0,pi/2) (the "symmetric branch") fails to be continuous hence fails to be differentiable at x = 0, it is released from the conclusion of the theorem.

However, it IS true that f(x) = pi/2 - arctan(x) on (0,+oo) and that f(x) = -pi/2 - arctan(x) on (-oo,0). On each of those intervals, the theorem holds true ... just for different constants for each interval!

This is typical behavior for functions with discontinuous derivatives. Consider the derivative of int(x) and its relationship to g(x) = C with C constant.

---

In addition to Kevin's comments, I want to give an aesthetic argument and a pragmatic argument for using the "symmetric branch."

Aesthetic: By taking this branch, we have the tidy rule that odd trig functions are inverted on the restricted domain (-pi/2, pi/2) (open or closed as appropriate), while even trig functions are inverted on the restricted domain (0,pi).

The continuous branch breaks the rule, which is not bad math, but is less tidy.

Pragmatic: On this branch, arccot(x) = arctan(1/x), x ≠ 0, in keeping with arcsec(x) = arccos(1/x) and arccsc(x) = arcsin(1/x).

This identity fails to hold on the continuous branch with range (0,pi).

---

On the downside, the symmetric branch fails to be differentiable at x = 0, which is disappointing since the computed derivative (arccot(x))' = -1/(1+x^2) actually has a value at this point. That is to my mind the strongest argument for using the continuous branch.

16 May 2016 at 8:38 pm [Comment permalink]

Straight and simple. Mathcad is correct there

24 May 2016 at 3:46 pm [Comment permalink]

If continuity of arccot(x) is the problem for the range (-pi/2,pi/2]-{0}, then by this reason the functions arcsec(x) and arccosec(x) are also have the same problem then why we consider them and why not arccot(x).

31 Jul 2016 at 4:32 pm [Comment permalink]

Extremely well written article. However, in my opinion, arccot x defined for 0 to pi is more correct than the other, and here's why.

arccot x + arctan x = pi/2. Therefore, the only way this relation is satisfied, is if the domain is constrained to 0 to pi.

This reason can't hold for the first interpretation, and hence is erroneous.

10 Aug 2017 at 5:14 pm [Comment permalink]

[…] попаднах на статия с много добро попадение свързано с функцията arccotg(x). В нея Мъри разглежда две възможни интерпретации на […]

12 Aug 2018 at 10:38 pm [Comment permalink]

If you look at this from a geometric standpoint wouldn't you expect that arccot(x/-y) = arctan(-y/x)? It seems that by using the domain [0, pi] we are losing the reciprocal property for tangent and cotangent.

13 Aug 2018 at 10:30 am [Comment permalink]

@Lorraine: Now that's an interesting perspective!

10 Feb 2021 at 12:54 pm [Comment permalink]

Many math softwares prefer second graph because if you input negative values to the arccot(x), it will give you smaller value which is closest to zero. Many functions such as logarithms, inverse trigs, power roots and so on which has no unique answer or in other word multiple values. So we have to choose one answer with some restriction known as the "principal value" which has to be smallest as possible in other word it is closest to zero. If there are more than one value closest to zero, choose the value having the most positive real part, then if there are still two answers with the same greatest positive real part value, choose the one with positive imaginary part.

For example, if you use first graph and input arccot(-1), you will get 3π/4, but if you use the second graph, the result of arccot(-1) is -π/4 which is closer to zero, thus it is the principal value of arccot(-1).

Also arccot(x) is defined as arctan(1/x) (you can prove it by drawing a triangle and deriving some tangent and cotangent formulas), if you plug -√3 in arccot(x) then it is -π/3 as same as arctan(-1/√3). If you use the first graph once again, it will be 2π/3 and it is farther from zero than -π/3.

Meanwhile, it is discontinous at x=0, but there has been convention that arccot(0) = π/2 and limit x to 0- arccot(x) = -π/2. It's okay to be discontinous as long as suitable with other functions. That's why I prefer the second alternative.

15 Nov 2022 at 9:26 am [Comment permalink]

Many thanks for the interpretation. I came across this issue tonight working in my Schaum's Analytic Geometry in one of the supplementary problems of chapter 11, and I got the same discontinuous hand drawn graph for y=arccot (x/2) by just naively taking x values, dividing them by 2 and inverting before taking the arctan of the new value on a calculator, but I double check each problem on completion at Desmos, and they show the continuous graph, so I spent about 20 minutes thinking about it, knowing that y values can be negative and positive, and so actually looked at a graph of y=cot x/2 and then it did hit me why I was getting a perfectly valid answer that didn't match another perfectly valid answer.

17 Feb 2023 at 10:34 am [Comment permalink]

Hello I am a student of Chemical Engineering currently studying second semester at the Universidad Veracruzana, my professor of calculus of a variable made me investigate about inverse trigonometrics, and this article seemed very interesting. Could you tell me where I can find more information about it?

sorry for my bad English